What are the duties of a director?

In Mauritius, the duties of directors are widely set out in our Companies Act 2001, namely under Section 143, which include the following duties:

- To exercise their powers honestly in good faith in the best interests of the company and for the respective purposes for which such powers are explicitly or impliedly conferred;

- To exercise the degree of care, diligence and skill that a reasonably prudent person would exercise in comparable circumstances;

- To account to the company for any monetary gain, or the value of any other gain or advantage, obtained by them in connection with the exercise of their powers, or by reason of their position as directors of the company;

- Not to make use of or disclose any confidential information received by them on behalf of the company as directors otherwise than as authorised by the law;

- Not to compete with the company or become a director or officer of a competing company, unless it is approved by the company;

- To disclose their interests where they are interested in a transaction to which the company is a party;

- Not to use any assets of the company for any illegal purpose and not to do, or knowingly allow to be done, anything by which the company’s assets may be damaged or lost, otherwise than in the ordinary course of carrying or its business;

- To transfer forthwith to the company all cash or assets acquired on its behalf, whether before or after its incorporation, or as the result of employing its cash or assets, and until such transfer is effected to hold such cash or assets on behalf of the company and to use it only for the purposes of the company.

The duties owed by directors are vast and it is clear that the legislator in including such a broad definition of directors’ duties in the Companies Act, sought to ensure that a director cannot act in any improper or dishonest manner. However, it is important to note that as per the law, these duties are owed by directors mainly to the company and secondly, to the shareholders. Such duties are not therefore owed to any third party.

Indeed, as per the well-established principle set out in the decision of the House of Lords in Salomon v. A. Salomon & Co. Ltd. [1897] AC 22, a duly incorporated company has a separate legal personality and consequently it is responsible for and should be sued in its own name in respect of its debts and liabilities. This takes us to the concept of the “veil of incorporation” whereby a company has a separate legal identity from its directors and as the company is a legal person, it is the entity which will be sued and the directors are normally protected from being sued as they are behind the company. This, of course, comes with a number of exceptions, the first one being the cases specified under the Companies Act whereby a director can either be sued by the company itself or by a shareholder or group of shareholders for breach of director’s duties.

Can a director be sued personally by a third party for breach of duty or abuse of his powers?

It is indeed an interesting question which arises from the principle of ‘veil of incorporation’. To what extent can a director be held liable for his or her unlawful acts and doings? The personal liability of a director is generally to their own company and in an insolvency situation, to the general body of creditors collectively as represented by the receiver Manager or the liquidator, but not to individual creditors.

However, in the event that the director departs from his duties and acts outside of his normal functions as a director, such as committing fraud or theft with the intention of engaging in a criminal act, one should consider the application of Article 1382 of the Mauritius Civil Code and thus the lifting of the veil of incorporation. Torts which are sufficiently particularised and which can be proved in court will lead to lifting the veil of incorporation, opening the door for a creditor to sue directors for breach of duty.

the veil of incorporation

Lifting the veil of incorporation (or piercing the corporate veil) means disregarding the corporate personality and the company’s separate legal entity to look behind the company and the people in control of it. Simply put into perspective, in the event of a dishonest or fraudulent act, the individuals in control will not be able to take advantage and shelter behind the corporate veil. The court will look beyond the veil and pierce the corporate veil to hold the directors liable for the misuse of their powers and breach of their duties.

In Littlewoods Mail Order Stores v Inland Revenue Commissioners [1969] 1 WLR 1241, Lord Denning explained:

‘The doctrine laid down in Salomon v Salomon has to be watched very carefully. It has often been supposed to cast a veil over the personality of a limited company through which the courts cannot see. But that is not true. The courts can and often do draw aside the veil. They can, and often do, pull off the mask. They look to see what really lies behind’

In a ruling given in the matter of Ireland Blyth Limited v/s Dodea Edhoo Paulina (2000 MRC 9), the learned Judge stated that this case would be a fit case for the lifting of the veil of incorporation as having regard to the shareholding (the respondent being the holder of all but one of the shares of the Company) and the functions of managing director of the respondent, it can but be said that the respondent is making an abuse of the fact of incorporation, and that the company and herself are to all intents and purposes one and the same. Therefore, it can be said that if a director is using a company as a sham just to evade his responsibilities, the Courts will consider the whole case and should sufficient evidence be available to prove that the director is seeking to use the company as a sham, the Courts may be inclined to lift the veil of incorporation, in which case the said director may then be found to be personally liable.

In Rory Kenneth Dunoon Kirk v The Bay (Holding) Limited 2013 SCJ 108, the Court considered the personal liability of directors and stated that authorities show “that a director may be personally liable in tort, for ‘wrongful trading’ under English Law, for a clearly particularised “faute” outside the exercise of his 3 functions as director under French Law, or in an insolvency situation under our own Companies Act 2001. The jurisprudence considered also shows that an action in tort is available against a director personally under tightly circumscribed conditions”.

The learned Judge further stated that French jurisprudence under Article 1382 of the French Civil Code of which Article 1382 of our own Civil Code is a replica, shows that an action may be directed against a director personally, based on a “faute” committed in the course of his acts or omissions as representative of a company, but whilst acting outside his normal functions as a director. For example it is not part of the functions of a director, qua director to engage in fraud or theft, with the requisite clear intention to defraud, or steal from, a third party. In doing so he therefore engages his personal liability because it is not part of the ordinary objects or rules of companies for them to commit fraud or to steal. A director who chooses to do so is acting as it were “on a frolic of his own”, and it is not the company, but the director who has to answer for such acts (vide the highlighted parts of note 87 of Manuel Pratique de la Société à responsabilité Limitée by Andre Moreau, under the heading Limitation de la responsabilité des associés).

The question of director’s personal liability was not fully debated on in that case as it was prematurely raised and further evidence needed to be adduced. However, we can conclude that the Courts in Mauritius will not blindly allow directors of a company to hide behind the veil of incorporation and will consider all factors and evidence available in considering whether a director’s conduct is faulty and therefore gives rise to personal liability.

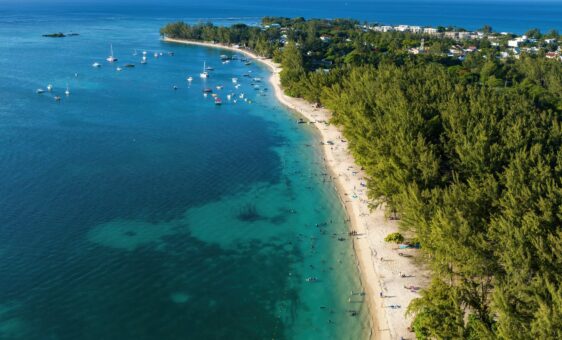

Locations

Services

Corporate, Dispute Resolution, Arbitration & Alternative Dispute Resolution, Regulatory Disputes, Fraud & Asset Tracing

Sectors

Type

Can a Director Be Sued Personally for Breach of Duty or Abuse of His Powers?

Yes, they can. Courts in Mauritius will not blindly allow directors of a company to hide behind the veil of incorporation and will consider all factors and evidence available in considering whether a director’s conduct is faulty and therefore gives rise to personal liability.